A Wondrous Fellow Appears Out of the Darkness

The Way of the Fool: Part II

A Series On the Inwardness of Becoming

Part II: A Wondrous Fellow Appears Out of the Darkness

Part III: Wholeness is the Fool’s Business

Part IV: A Medley of Fools Heralds the Journey Within the Journey

Part V: The Quality of the Fool

Part VI: Pathways through the Mandelbrot Set

“There are human beings living in isolation and loneliness in the society of men who realise suddenly that they belong to the Fool.”

– Cecil Collins

The Boy experienced from early on in life a sense of communion with all things which moved him so deeply that he has never since forgotten it. He called these experiences the Stirring. He once wrote a story called The Tale of Two Tomorrows in which he attempted to express these experiences as best he was then able to:

He remembered every little detail about the things and creatures, the moments that had come and gone. These were the moments when he had felt the Stirring. They were the whispers of a feeling, gone before he could quite grasp them, yet subtle and fleeting as they may have been, they stirred him and to the Boy’s mind, they were the dreams of the Giant who lay asleep in all things. He had seen him asleep in the field of wheat as the wind tugged at his hair, seen him snooze in the dappled light of the glade, in the rockfaces of the tors, seen his wrinkled face in the bark of trees, his nostrils flaring in a pile of leaves. It was the work of the Boy and the Horse to explore the Giant’s dreams and to capture their essence in this way.

In his story, the Boy and his companion, the White Winged Horse, make it their work to explore the Giant’s dreams and to capture their essence in glass jars which to anyone else would appear empty. However:

On closer inspection, his collection of jars contained sand grains, specks of dust, air, water. There was a preserving jar which contained the dappled light of the woods and another with the summer breeze of the open moorland. A small jar contained the leap across the brook on the back of his White Winged Horse. One jar contained a water boatman as the sunlight glistened in the stream.

The Boy had taken great care to capture only the moment, not the river boatman itself. He had taken the same care with the flight of the kingfisher darting upstream, the taste of the first steaming crust of bread he had baked in the oven in the glade, and the sound of the owl at new moon.

The collection of moments in a vast number of glass jars in his outer life –at one point the story mentions 1,039– mirrors his inner experiences which add up in such a way that he finds himself encouraged to understand his experience as real despite the general tendency for them not to be reflected in his more immediate outer world encounters at home, at school or otherwise. The sense of communion with the world at large thus leads to a simultaneous and paradoxical sense of being separate from his fellow men, of not fitting in, of finding himself on the outside looking in.

In the Boy’s story, there is a particular moment of conscious awakening to his situation. On his way to school together with his horse, the Boy spots a sycamore seed floating through the air. He kneels by a puddle to pick it up and put it in one of his jars.

When he had stored it away again safely, his gaze fell on a face that looked back at him from the puddle. It was the face of the Giant. The Giant was awake, and he was smiling at the Boy, but it appeared that he might also be crying. The Boy could not tell for certain as the Giant seemed to shudder and fade. He looked up and then realised what was causing the tremors which were disturbing the puddle. His Horse was galloping away. The Boy screamed. The Horse turned its head back. The Boy saw that the Horse felt a strong urge to return to him. But a mighty will pulled its eyes away from the Boy and toward the open skies beyond the City, galloped up the street, spread its wings and took flight.

The moment of conscious awakening was thus also a moment of painful falling from grace: deserted even by his closest companion, he had to face the outer reality of school which represented the prevailing institutionalised mindset and attitude of the place and times into which he was born and where he was perfectly capable of performing well but where he did not find his inner experiences reflected either in what he learned or in the contact with his fellow pupils and his teachers.

What on the outside expressed itself as carrying books with him wherever he went, reading well beyond his age, visiting the library frequently or taking numerous classes outside of a busy school schedule, on the inside existed as an insatiable interest in and a burning pursuit of a certain kind of quest concerning the Nature of the human being and of the world, or in the words of the Boy, of the Giant as his experiences led him to question the usual distinction between himself and the rest of the world as populated with things with definite hard edges and boundaries.

His quests were tied up with questions to which he was looking for answers; though the quest may somehow and ineffably have been clear even if the questions were not.

There were hard questions that were immediate and personal: ‘Why do I dream of a crying boy in the woods baking bread?’, ‘Why did the Mother burn my hand in the scalding porridge?’, ‘Why do I try and escape through the blackholes in the wall?’, ‘Why do I dream of large scissors cutting into my legs?’

And there were even harder questions which were concerned with the Nature of time and space, the shape of the Universe, and whether we lived or whether we were lived by some greater being: ‘Whence do I come from?’, ‘Where am I going?’ and ‘How shall I live?’

With his White Winged Horse gone, the Boy was left with the experience of a gaping flesh wound not dissimilar to the one experienced in his recurring dream of the giant scissors. It was the kind of wound Adonis and Odysseus experienced when wounded by a boar. It was the wound that is both mortal (when looking into the past) and life-giving (when looking into the future). It was the place that becomes a womb in the psyche and opens the world to the mundus imaginalis, the inner world of images, pictures and symbols, the world of imagination.

As Marie-Louise von Franz notes:

The actual processes of individuation – the conscious coming-to-terms with one’s own inner centre (psychic nucleus) or Self – generally begins with a wounding of the personality.

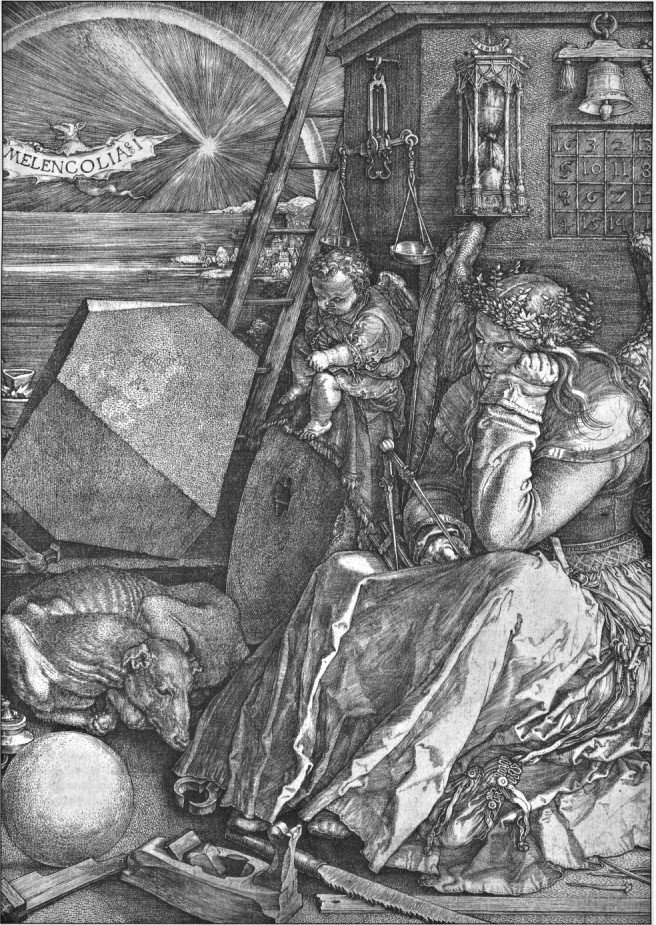

And so, a chasm opened up in the Boy between the numerous personas with which he met his external world and this inner space which was at first almost entirely dark and into which he retreated often even when he was engaged in the outer world. In this place, which at first might well have been described as a cave, he encountered a character which would become central to his inner life as a guide on a long journey. The Boy would come to know this wondrous and elusive fellow who came out of the darkness as the Fool.

End of Part II.

The Way of the Fool – Part III

Wholeness is the Fool’s Business

To continue to part III click here:

Wholeness is the Fool’s Business