The Boy had been at sea all of his life. He had been aboard a sturdy three-masted ship, a mighty barque. The Boy did not know he was at sea. He did not know he was aboard a ship. Until, that day, when he awoke to find himself playing on the deck in the full sun, when the vessel was at anchor in a bay.

The Boy could see the white sand of the beaches and the lush green of the woods covering the rolling hills beyond, and the sight of the curved shoreline stirred something in the Boy. He wandered up and down the long boards of the deck which he had scrubbed only yesterday. He roamed the vast spaces below decks, following a yearning that rose within him.

It was when he climbed back up and out on to the foredeck that he found that he was alone. The Boy realised that he had been alone for some time, that there was no one else on the ship, and that he was lonely and had been so for a very long time, not knowing that he had been.

No sooner had he tasted but a first drop of his loneliness, the Boy found himself distracted from following the feeling any further by a noise which appeared to him like a fountain of water splashing into the sea.

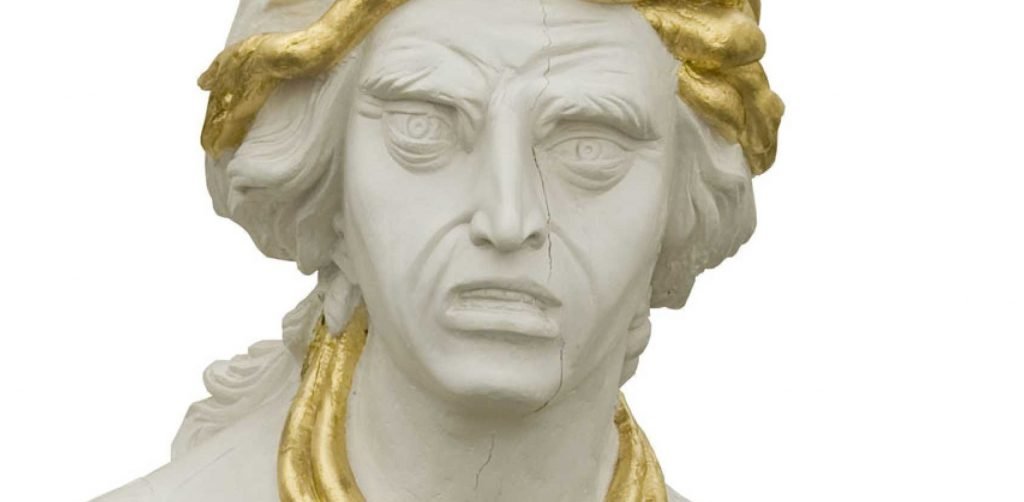

The Boy followed the sound and searched the vessel until he found an enormous figurehead at the prow of the barque which was spewing water out of her mouth and into the sea. He saw that she was quite alive.

“Who are you?” said the Boy to the figurehead.

“I am the Mother,” spoke the figurehead. “And you are the Boy. You belong here on the ship with me. Everything you need is here.”

While she spoke, the Boy saw black ribbons in the water which writhed like snakes as they fell to the sea. Curious about what he had seen, the Boy climbed back up the rigging from where he had come close to the figurehead to stare at the waters below: the sea was full of those serpents which he had seen escape the Mother’s lips as though the sea on which he sailed was but a sea of the Mother’s words. For a moment it crossed the Boy’s mind that the serpents might be guarding the ship.

The Boy cooked for the Mother and cleaned the ship. He woke her in the morning and she settled him to sleep. In his spare time, he played on deck but the longing had been stirred so deeply within him that he could not let go of the thought of swimming across to the shore and he found himself staring over the railing as he nursed the growing wish inside of him.

That night, he could not go to sleep.

“What is it?” asked the Motherhead.

The Boy could not respond for he was anxious that he would upset the Mother.

“You can tell me anything. What is on your mind?” encouraged the Motherhead.

Eventually, the Boy said shyly: “I would like to go ashore.”

The night air had been warm. Now it was cold. The surface of the sea had been smooth as glass. Now it bristled.

“Why would you want to go ashore? I provide everything you could possibly need. It is not safe for you. You belong here with me,” said the Motherhead, and she did what she always did whenever he spoke even the smallest word of himself: she cried.

“You are right,” said the Boy and pretended to go to sleep, but instead he began to make a plan.

The next day, the Boy served breakfast and when she was eating, he stole away, took off his clothes and jumped. In an instant, as soon as his dive split the surface of the waters, the sea was writhing with serpents as his skin was crawling with the sharpest guilt. The figurehead was wailing and her tears caused the waters to boil and her scream gave birth to a serpent so huge, it wrapped itself around the entire barque at least twice. The fire in the Boy which had burnt so brightly with the wish to swim ashore had not only been extinguished: The stone-cold eyes of the sea-serpent sought out the Boy’s face and petrified him as it stung him with its tail with a poison that froze his blood.

The Boys limbs trembled and he was so cold he could hardly move as he climbed back aboard, remorseful and defeated. He crawled as close to the figurehead as he could, bedraggled, shivering, freezing cold.

“What have I done that you should treat me like this?” she said. But before the Boy could speak, she cried again. And when she cried as she cried, the Boy felt dizzy and the words he wanted to speak lost their shape and swam before his mind’s eye.

“But… I… I would… I would so like to… I would so like to swim ashore… explore the land”, the Boy stammered.

“Never speak to me like that again,” said the Motherhead.

The Boy did not want to say it but he could not else for he had practised it too often. “I am sorry,” said the Boy. “It is my fault. I should have thought of you before myself.”

This soothed the Motherhead.

“I know you better than you know yourself,” she said. “You will grow to be a gentle man. You will overcome your rage. You will realise that you belong here with me.”

For a while, every time the Boy as much as thought about the shore, the figurehead would send tears into the sea and cause a storm. The word-serpents would writhe about the barque and the Boy would freeze in shame.

Yet, somewhere, somehow, the more the Boy was stung, the more the longing in him stirred too, and while he grew more sullen, he grew stronger also. One day, quite how the Boy did not know, the Motherhead’s words and tears, her wailing and hurting which he had endured year-in, year-out, while they had shaped him, scarred him, they did not quite sting him as mortally as they had before, and he managed to swim ashore.

As the Boy climbed out of the sea, he wanted to cry, exhausted not so much of swimming but of having borne his life as a captive on the barque. He could not cry because to cry would be to be like the Motherhead. His sadness was real but it was his and his alone. He would keep it on the inside so that it would not have to affect anyone else like her sadness had affected him.

But, as the wailing coming from the vessel anchored in the bay continued into night and day as loud on the beach as it had been on the barque, a fierce wish in the Boy arose to silence it, once and for all. And so, before he explored the lands he had fought for, so long and so hard, he made a club from driftwood which he found on the shore and fastened it to his belt.

Then, under cover of night, the Boy returned to the barque and climbed up the anchor chain, and holding on to the railing, beat her with the club, and yet she would not stop for another day and night and another day, until until eventually, the continued beating made her come lose and she fell into the waters below. Yet she was still alive, and the Boy had to drag her back to the beach where he made a fire with her wood.

She burnt for seven days and seven nights, and on the eighth day the figurehead was no more. Free of her hold, the Boy was also free to grieve the Motherhead. But his tears of deep sadness for her loss were not tinged with remorse, for he felt her sting still. Yet, now, he felt the stirring move him more, and feeling himself so truly, his tears did not extinguish the fire but rather made it transfer into him.

Forged as he was by her sting and his stirring, he arose, broken, yet drawn forward by some future wholeness.